Bratislava, 300 yards and Sidewalks

Or, the need to design with children and young people in mind

“There is no point in planning for play on sidewalks unless the sidewalks are used for a wide variety of other purposes and by a wide variety of other people too. These uses need each other for proper surveillance, for a public life of some vitality, and for general interest. If sidewalks on a lively street are sufficiently wide, play flourishes mightily right along with other uses.” – Jane Jacobs

Aloha!

Travel with me, this week, to Bratislava of all places where a ‘Start with Children’ summit has recently reflected on the increasing interest internationally towards child-centred urban planning.

Hurrah!

If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, you’ll know my thoughts on how designing for the most vulnerable can actually improve life for everyone else.

But heck. While we wait for the rest of the placemaking world to catch up, let’s reflect on the fact this is a positive step forward. The Urban Design Group have helpfully summarised the main points from the summit, which I include here for your delectation (thank you UDG!):

Cities are starting to focus on children to make things healthier and fairer for everyone. It is happening because of an increasing concern about traffic dangers, pollution, not enough play areas, and the need to deal with climate change.

The view is that if a city works well for children (safe, clean, easy to get around), it's a good sign that it will work well for everyone.

While the UK sees growing interest in child-friendly concepts (such as 15-minute cities, school streets), progress is patchy and hindered by car-centric planning and high car parking requirements in development.

UK thinkers and practitioners are influential internationally, with initiatives like Playing Out and London's play space policies serving as inspiration, though mainstream adoption faces challenges.

Need for Systemic Change: Overcoming the normalization of car ownership and use is a key global challenge to truly prioritize child-friendly and inclusive urban environments.

Sharing Stories & Advocacy: Practitioners play a vital role in sharing successful examples, advocating for policy changes, and highlighting the benefits of prioritizing children in urban design.

The challenges to my mind continue to revolve around our love of car-centric planning – motonormativity.

How many more summits and conferences do we need before we consistently start designing for people – and in particular the most vulnerable among us – rather than cars and the turning circle of a bin lorry?

Thankfully, there are signs of hope.

It turns out that London Borough of Hackney have produced a ‘Child-Friendly Places’ SPD. Considering it was adopted in 2021 I’m a little late to the party on this one but never mind!

The document starts out by stating it is for “… children and young people who live, study, visit and play in Hackney…” – fantastic! – as well as planners, developers, neighbourhood forums and the usual cabal of professionals who should be looking at SPDs when making decisions.

I would suggest that in the next iteration of this SPD, highways officers get a specific mention considering that children have a “… right to safe, easy and independent mobility…” Can we please remind the engineers that the local plan and its supporting SPDs are council-wide documents and “not just" for the planners?

Aaaaaaaaanyway…

The document provides guidance on the way doorsteps, streets and destinations are designed to ensure young people can get about independently and identifies eight principles of good design including:

2 – Doorstep Play: to provide easily accessible and overlooked space for play and social interactions immediately outside the front door

3 – Play on the way: to provide multi-generational opportunities for informal play, things to see and do around the neighbourhood beyond designated parks and playgrounds

4 – Streets for people: to ensure that children, young people and their families can safely and easily move through Hackney by sustainable modes of transport such as walking, cycling or public transport

I particularly like the concept of doorstep play and having some fun and inclusive play space right outside the home. If there was this instead of bins and pavement parking (as a London Borough pavement parking should not be an issue in Hackney, but it certainly is where I live), what a different world we would live in!

But this focus on children isn’t new.

Last week I focussed on the work of Jane Jacobs. But what I didn’t mention in that piece was the chapter in ‘Death and Life’ on the uses of sidewalks: assimilating children.

Jacobs explains that sidewalks are safer spaces for children to play than the manicured parks and playgrounds provided in the ‘improved’ and gentrified housing projects. These formal spaces were considered more dangerous – even by children themselves – than the remaining so called ‘slum’ streets that surround them. Such parks and playgrounds become the scene for anti-social behaviour because they are not well overlooked and there are no, what Jacobs calls, “public characters” – shop keepers, residents, workers, commuters etc. – casually policing what’s going on.

A good street, on the other hand, is generally occupied by people going about their day and inadvertently keeping an eye on things.

The children at the time Jacobs wrote Death and Life had the same ideas as young people today: that if they want to get up to serious mischief, the parks and playgrounds are the place to go because there are no or very few adults there.

It is on a vibrant street where you can’t get away with much – but you’ll also have people looking out for you. As Jacobs points out:

“People must take a modicum of public responsibility for each other even if they have no ties to each other. This is a lesson nobody learns by being told.”

On a busy, vibrant street you can’t help but start supervising the “… incidental play of children and assimilate children into city society” while going to work, enjoying a coffee at the pavement café or mindlessly staring out of the window.

So by focussing on children, Hackney is actually doing something really good for its young people and for society as a whole.

Instead of focussing only on providing formal play space to whatever specification their open-space policies require, they are seeking to make the whole place interesting from the moment you leave the house to the moment you arrive at your destination. That’s a very good thing.

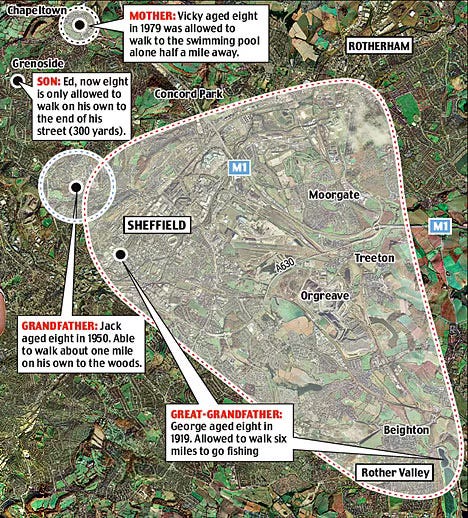

If they can fully achieve Principle 4 – Streets for people – we might yet see a return of children roaming independently as their grand-parents and great-grand-parents did. It’s a heck of a long shot. But when you consider children in the UK have basically lost the right to roam in four generations, it puts it in perspective:

And it is through this consistent ‘learning’ of how to behave in the street and avoid the ire of the corner-shop keeper that children learn how to get along in the messy, diverse and multi-cultural world in which we live. The scourge of pavement parking outside of London – where it is already banned – prevents so much informal play and has got to stop.

And so, in summing up, if we want to give children freedom and make it safe for them to roam and explore, here’s a final message from Jacobs to the officers at Hackney:

“There is no point in planning for play on sidewalks unless the sidewalks are used for a wide variety of other purposes and by a wide variety of other people too. These uses need each other for proper surveillance, for a public life of some vitality, and for general interest. If sidewalks on a lively street are sufficiently wide, play flourishes mightily right along with other uses. If the sidewalks are skimped, rope-jumping is the first play casualty. Roller-skating, tricycle and bicycle riding are the next casualties. The narrower the sidewalks, the more sedentary incidental play becomes. The more frequent too become sporadic forays by children into the vehicular roadways.”

Jacobs cited a sidewalk width of 10m as the ideal to accommodate all types of play, circulation and sidewalk life as well as trees to shade these activities but acknowledged this would be a luxury. Nevertheless, perhaps when Manual for Streets 3 is finally published, it should call for pavements to be at least a minimum of 3m wide (see the Hackney SPD) rather than the current 2m?

Question: Do we need explicit policies from the government to put child-centric planning front and centre?

#placemaking #urbandesigngroup #udg #cities #urbandesign #janejacbos #children #motonormativity #streets #streetsforpeople